The Making of Bubblegum Princess

Story Development, Part 2: Our corgis can fly!

It’s extremely frustrating when you know your picture book story is not quite working, but you don’t know why, or how to fix it. Maybe you’ve become wedded to the plot, or tangled in rhyme, or too fond of your characters to cause them any grief, but whatever the reason, being dissatisfied with your manuscript is a good thing because it’s an indication that you’ve grown as a writer and now know when something is not working and has to change.

When I got to that place, I sought a fresh perspective. I had already shared the story with friends who were accomplished screenwriters, and they had given helpful feedback, but I needed to hear from an expert — a professional picture book editor.

The Picture Book Whisperer

I found Marlo Garnsworthy on Book Editing Associates’ list of children’s book editors. Marlo has worked as an editor since 1990, she teaches writing for picture books and chapter books as a faculty member of the Rhode Island School of Design, and she is a published author and illustrator. I checked her website Wordy Birdie, found this fantastic post on the perils of rhyming verse, and decided she was perfect for Bubblegum Princess. So I sent her my 600 word manuscript. It was a mess — incorrect formatting, no address, no title or word count, numbered pages of text which I’d centered for some reason, wacky plot — but this was three years ago, she understood it was my first attempt at writing a picture book, and she was up for the challenge.

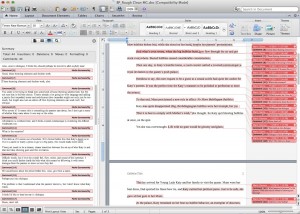

[Click to enlarge images.]

MS TEXT and SUGGESTED EDITS

About a week later, I received three documents: a 13 page critique, an MS with tracked changes of original text with suggested edits and comments, and a clean copy of the MS fully proofed with additional comments.

She kindly pointed out that my page count was not quite right:

It’s great that you have thought about how to paginate your text. This is a really important tool to use as you write picture books. It’s also great that you’re thinking in terms of double-page spreads, not single pages. However, standard picture books have 32 pages, not 24, so you’ll need to do some rethinking. You will not submit your text to publishers paginated, but as I said, it’s an important part of the writing and revision process. I will send a 32 page storyboard for you to use. (Sometimes you will see variation, but it is either because the author or illustrator is very well-established so the publishing houses can afford to spend more money on them, or the endpapers [the ones stuck to the cover] are illustrated and counted within the 32 pages.)

And she included quite a few helpful hints like these:

POV

If you stay in your protagonist’s POV, that means we cannot know what your other characters are thinking or feeling unless they show us by what they say in dialogue, or by what they do physically: facial expressions, movements, reactions etc. This was an issue in places. Try to avoid POV shifts, and certainly do not go into the parents’ or any other adults’ heads.

Language Style

Short, sharp sentences tend to increase tension. Longer, more lilting sentences tend to create a different feel altogether. I’d avoid the urge to break into a jaunty meter with end-rhymes, unless you do it near the end to speed up the pace before the climax.

Showing vs. Telling

Sally loved the beautiful flowers. She was bursting with excitement.

The writer tells us Sally is ‘bursting with excitement’. She might show us the same thing with:

Sally held the delicate pink rosebuds tightly to her chest. “Yippee!” she squealed as she danced around the room.

You’ll see the difference. It provides exactly the same information but shows, rather than tells the reader what Sally is feeling by the way she acts and her dialogue. It also shows us the flowers and allows us to judge whether they are beautiful (thereby avoiding one of the weakest adjectives in the English language: beautiful). Showing makes for much more interesting reading.

The Relationship between Image and Words

As you know, picture books are (by definition) illustrated, and pictures and text should work in tandem. A picture book text should not be able to completely stand alone without the illustrations. And the illustrations should not be just a back up to the story, but should carry equal weight in terms of storytelling. This is often one of the most difficult, yet essential, concepts for new picture book writers to grasp, but I felt you had a really good handle on it.

Here are excerpts from the MS followed by Marlo’s comments after the bracketed text.

(Next post, I’ll show how I incorporated her suggestions into the revised manuscript.)

Once upon a time, in a land not far from here, there lived a young lady named Katy.

A delightfully witty, extraordinarily kind, decidedly brilliant young lady was she.

[Once upon a time, in a land not far from here, there lived a young lady named Katy.] Consider not putting a page turn here. There’s not enough info about who Katy is to make the text strong enough on this first page.

[delightfully witty, extraordinarily kind, decidedly brilliant] Would be great if you (briefly) show us how she is these things. That will help kids understand what the words mean. Illustrations will help too, of course, but it’s difficult to illustrate delightfully witty and decidedly brilliant, so I feel the text could better illuminate these.

[was she] I’d avoid this backwards phrasing.

However, Katy had one habit Mum and Dad deemed utterly disgraceful, singularly silly, frightful and stupendously bad.

[However, Katy had one * habit] *Bad? Feels like it needs an adjective here.

I’d put a page turn here. That would create much more tension as readers wonder what the habit is. Then escalate the tension on the next double-page spread as her parents tell her how bad it is.

[Mum and Dad deemed it utterly disgraceful, singularly silly, frightful, and stupendously bad.] Stronger to break the sentence up. I would show us this in dialogue. Also, once in dialogue, I think this should perhaps be moved to after “awfully mad.”

Katy loved to blow bubblegum bubbles, and that made her parents awfully mad. She blew bubbles before bed, while she stood on her head, despite her parents’ protestations. And what’s even worse, when the big bubbles burst, goo flew through the air and got stuck everywhere. Busted bubbles caused considerable consternation.

[Katy loved to blow bubblegum bubbles, and that made her parents awfully mad. She blew bubbles before bed, while she stood on her head,] Good, these rhyming elements and rhythm work.

[despite her parents’ protestations. And what’s even worse, when the big bubbles burst,] These rhyming elements and rhythm work, also.

[goo flew through the air and got stuck everywhere. Busted bubbles caused considerable consternation.] You seem to be trying to break into some kind of loose rhyming scheme here, but I’m not sure that is the best choice. There’s already a lot going on with language and adding a jaunty (but imperfect) meter and end-rhymes (also imperfect) might not only just be too much, but might also turn an editor off. But rhyming elements can work well. See critique.

Then one day, to Katy’s humble home, a court courier carried a coveted communiqué: a royal invitation to the queen’s posh palace. Needless to say, this rare request to be a guest at a swank soirée had quite the cachet for Katy’s parents. It was the perfect time for Katy’s manners to be polished to perfection to meet the prince.

[Then one day, to Katy’s humble home, a court courier carried a coveted communiqué: a royal invitation to the queen’s posh palace.] Who covets it? It seems this is something the parents care about, but I don’t get a sense of whether Katy cares about it one way or the other. Alliteration is overdone here, and I think coveted communiqué is overdoing the difficult vocabulary too.

What is the occasion? This feels as if it comes out of nowhere. If it’s hinted before this that Katy’s desire is to live in a castle or marry a prince or go to a big party, this would make more sense. There just needs to be a cleaner, clearer transition between the set-up of who Katy is and that she likes chewing gum and this invitation.

[Needless to say, this rare request to be a guest at a swank soirée had quite the cachet for Katy’s parents.] Difficult words, but I love the overall feel, flow, meter, and sound of this sentence. I think you could further clarify for kids what this means by following it with some dialogue from the parents to show us how they feel.

[It was the perfect time for Katy’s manners to be polished to perfection to meet the prince.] We could know about the prince before this. Also, give him a name. Perhaps put into dialogue. The problem is that I understand what the parents’ desire is, but I don’t know what Katy wants.

To that end, Mum proclaimed a new rule in effect: No More Bubblegum Bubbles.

Katy was quite disappointed. Big, Brobdingnagian bubbles were her triumph, her joy.

But it was best to comply with Motherʼs wish, she thought. So Katy quit blowing bubbles at once, on the spot. Yet she became overwrought: Life would be gloomy and glum with no gum.

[To that end, Mum proclaimed a new rule in effect: No More Bubblegum Bubbles.] I think I’d like to hear her say it: dialogue.

[Katy was quite disappointed.] Show, don’t tell.

[Big, Brobdingnagian bubbles were her triumph, her joy.] This could go into dialogue.

[But it was best to comply with Motherʼs wish, she thought. So Katy quit blowing bubbles at once, on the spot. Yet she became overwrought: Life would be gloomy and glum with no gum.] “But it is best to comply with Mother’s wish,” she thought. So Katy quit blowing bubbles at once, on the spot. Yet she was overwrought. Life with no gum would be gloomy and glum. — Dialogue is fairly absent, and it’s needed, hence my changing this to internal discourse here. And why is it best? What does she want? Why? This hints at a deeper problem. What is it?

The story develops

With this critique in mind it became clear that it wasn’t important to keep the story tied to factual events. As well as having a strong narrative structure, the story must be entertaining. Each of Marlo’s examples were fun, engaging, and appealed to a picture book reader. So I examined the elements in the story, particularly the ending which was an unfortunate bit of storytelling: our heroine marries the prince and then has a baby. Did that happen in real life? Yes, and in traditional fairy tales this does happen, but after this first round of edits it was apparent that the story needed to change.

This could have been an agonizing experience, but at this early stage, it was liberating — I thought, if the characters were released from the constraints of real events, what would they do? Perhaps they would fly? Maybe corgis would giggle? Most importantly, I could fix that plot problem — her mum no longer had to chew gum, and I could look for a different culprit. That’s when I decided that Prince Will had blown the troubling bubble. It made perfect sense, this would now be how he and Kate met — to create a modern day fairy tale, history would have to be re-written.

Next in this series: Character Development – A Collaboration

SPECIAL NOTE!!!!

NOTE FROM BETH: Because of my summer blog hiatus coming up, Julie’s next post will be in September. See you then!

Previous Posts in the Series:

Part 1, How to Make a Picture Book, Series Intro

Part 2, Choosing your Illustrator/Choosing your Author

Part 3a, Story Development, part 1

Bios:

Julie Gribble was the first picture book author accepted into the Stony Brook Southampton Children’s Literature Fellows program and has been mentored by Emma Walton Hamilton and Cindy Kane Trumbore. She’s a full-time writer and a member of SCBWI, ChLA, BAFTA-NY Children’s Committee and is founder of KidLit TV an online visual resource for the greater kid lit community.

Lori Hanson received her Master of Fine Arts from the San Francisco Art Institute and served an apprenticeship under celebrated artist Gregory Gillespie. She’s a member of SCBWI.

Bubblegum Princess, a picture book inspired by the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, has received a First Place Royal Dragonfly Children’s Picture Book Award, a nomination for a Cybils Award, and is Story Monster Approved!

NY Media Works: www.nymediaworks.com

Lori Hanson’s website: http://www.rosengrove.com/bubblegum-princess.html

Bubblegum Princess website: http://nymediaworks.com/bubblegum-princess

Bubblegum Princess on Amazon: http://www.amazon.com/Bubblegum-Princess-Julie-Gribble/dp/0989091406

Bubblegum Princess in Square Market: https://squareup.com/market/ny-media-works-llc/bubblegum-princess

Please feel free to ask any questions! I’m always available to help.

This was extremely helpful. Wish I could just print it out and have it in hand as I revise. Lots of good advice. Julie gave much thought to the MS and added excellent examples of how and why something needed improvement. Enjoyed the series. Will refer back. I have a story that I wrote and like, but I know something is missing and I haven’t put my finger on it. So I set it aside for a while and am revising a recently edited MS that has my full attention. Thank you Julie and Beth!

Patricia – putting aside your story, even if just for a little while, is a great idea. Here’s the place where I usually get stuck: determining WHY the MC wants what they want. I have to dig deep to get unstuck. And that’s where I discover the reason I wrote the story in the first place. How about you?

Wonderful post as always! Full of information. Thanks for being so generous!

Thank you Miss Tracey!

Have fun during your summer! 😀 This is an excellent post! 😀

Thank you Erik! Marlo’s advice was so helpful.

This was lovely Julie and Beth. I’m searching for Parts 1 and 2 – can you please direct me to the earlier installments? Thanks!

Definitely! I should have had the links in the post, and will rectify it. Thanks, Cathy!

Part 1: https://www.bethstilborn.com/how-to-make-a-picture-book-the-making-of-bubblegum-princess-part-1-series-intro/

Part 2: https://www.bethstilborn.com/how-to-make-a-picture-book-the-making-of-bubblegum-princess-choosing-your-illustratorchoosing-your-author/

Part 3a: https://www.bethstilborn.com/how-to-make-a-picture-book-part-3/

TY!

You’re welcome!

Thank you Cathy! And just so folks know, I asked Marlo in advance if I could share this excerpt of our process. I’m glad she said yes!