Reading to learn, reading to seek justice — in the spirit of #WeNeedDiverseBooks, I’m exploring two books today about Residential Schools in Canada. First Nations children were still being taken from their homes and forced to attend residential schools when I was in school. I am grateful that these schools are no longer in existence. This is a long post. I hope you’ll read the whole thing.

All over Canada, for over 100 years, beginning in the 19th century and continuing until the last such school closed in 1996, the government tore First Nations children from their families, their culture, their traditional ways, and attempted to remake them in the white image. Not only was it not successful, it has damaged survivors and our society as a whole for generations.

Quoting an article about the history of the schools from the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation) website, “in all, about 150,000 First Nation, Inuit and Métis children were removed from their communities and forced to attend the schools.” (Link in resource list below.)

Residential Schools are a huge scar on our nation’s history, and they leave many internal and external scars on the survivors. Canada has been going through a process called the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, as we, together, try to heal the wounds.

I’ve recently read two children’s books, one a picture book and one a middle grade novel, that open up the subject for today’s children, to show them what it was like and hopefully to start dialogue between children and adults about racism and the ways racism mars both the perpetrator and the victim.

I will give some resources at the end of this post, and I urge you to take a look at them.

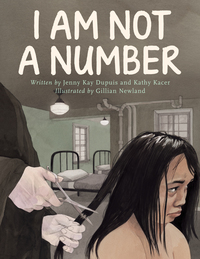

Author: Jenny Kay Dupuis and Kathy Kacer

Illustrator: Gillian Newland

Publisher: Toronto: Second Story Press, 2016

Genre: Picture book

Audience Age: 7-10

Theme: Residential Schools, First Nations people, human rights violations

Opening Sentences: The dark figure, backlit by the sun, filled the doorway of our home on Nippising Reserve Number 10. “I’m here for the children,” the shadowy giant said, pointing a long finger at me.

Synopsis: Irene Couchie was eight years old the day the Indian agent came and took her and two of her brothers away from their family to go to residential school.

She was separated from her brothers (girls and boys rarely were allowed to mingle), her long hair was cut, they were bathed and told, “Make sure to scrub all the brown off.”

When she gave her name, she was told, “We don’t use names here. All students are known by numbers. You are 759.” She was punished painfully for using her native Ojibwe language.

She dreamed of being home, of being with her family, of hearing the meadowlarks. “I yearned to spread my arms wide, as if I were ready to soar, like them. I longed to fly away, but for me there was no escape.”

This book is based on the true story of the author’s grandmother’s year in residential school. It does not sugarcoat the harshness of the experience. It is well written and vividly illustrated, and is an excellent introduction to this part of our shared history.

I would encourage adults to read the book first, before reading it with kids, or before kids read it for themselves, in order to be prepared to discuss the difficult situations that are portrayed in the book, and to answer the questions kids are sure to have. But I do urge you and your kids to read this book. It is important to know what so many of our Canadian (and American) brothers and sisters have been through.

There is a brief video of the author speaking about the book at this link.

~ ~ ~

Author: Shirley Sterling

Publisher: Toronto: Groundwood Books/House of Anansi Press, 1992. (Twentieth printing 2016)

Genre: Middle grade novel

Audience Age: 9-12

Theme: Residential schools, First Nations, human rights violations

Opening Sentences: Thursday, September 11, 1958. Kalamak Indian Residential School. Today my teacher Mr. Oiko taught us how to write journals. … I like journals because I love writing whatever I want. … My name is Martha Stone. I am twelve years old in grade six at the Kalamak Indian Residential School.

Synopsis: As the opening sentences suggest, the book is written as a journal, one year in the life of twelve-year-old Seepeetza – or Martha, as the nuns at the school insist she be called.

Through the memories she writes in her journal along with accounts of the day, we learn that she was taken to residential school when she was five.

As was the case with far too many residential school children, she knew abuse and harsh punishment, as well as being separated from her family and her culture. Told by the nuns that there were devils under her bed, she was afraid to get up in the night to go to the bathroom then when she inevitably wet the bed, she was strapped and made to wear a sign saying “I am a dirty wetbed.”

When I read that she was part of the dancing group, I foolishly thought this meant that some of the students were allowed to do their own culture’s dances. Far from it. They were taught the dances of other cultures, such as Irish dance, and performed in many folk dance competitions. It is telling that reflecting on a photo taken of her, smiling, at one of these competitions, she said “How can I look happy when I’m scared all the time?”

No child should have to be scared all the time. Although the book doesn’t mention the worst abuses that survivors tell of, there is enough that we can see that life was difficult for these children.

Because the book covers one year in her life, we also see the contrast between her all-too-brief vacations at home and her time at school. Like little Irene in the other book, I’m sure there were many times she wished she could fly away.

This book is based on the author’s own experiences in residential school in the 1950s. As the blurb on the back cover says, it “is a moving account of one of the most blatant expressions of racism in the history of Canada.”

Again, I would encourage people to read this book with their kids, anticipating their questions and preparing for them. But again, I do urge people to read this book.

Resources for adults:

A brief history of residential schools in Canada, from the CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Corporation), mentioned earlier in this post.

A reconciliation reading list, compiled by the CBC.

The document They Came for the Children, from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (note that this document is in the public domain, and sharing and quoting is permitted).

The website of an exhibition of photographs and stories from residential school survivors, Where are the Children? Healing the Legacy of the Residential Schools. (Note that there is a warning on the site that some images may be disturbing.)

Resources to use with kids:

Resources for bringing the story of residential schools into the classroom, from the website Active History.

A list of resources compiled by the Abbotsford, British Columbia, School District’s Aboriginal Education department.

Two very important books. Thanks for reviewing them, Beth. How did people, in our lifetime, think this was the right thing to do?

It really makes a person wonder how people thought this was the right thing to do. I had no idea at the time just how awful the residential school experience was — were we just unaware? Or were we (as a society) consciously avoiding the question?

I’m so grateful that finally, finally, work is being done toward learning the truth and helping the healing process.

Much needed post. Have you seen Gord Downey’s latst – “The Secret Path”? Amazing, gut-wrenching.

Thank you, Bev. I will put “The Secret Path” on my to-be-read list.

As I said on FB, I wish we had something like the Truth and Reconciliation Committee in the US – instead we have the DAPL and Native Americans as sports mascots.

Our local public schools – not far from the Seminole Reservation – have uniforms, and I understand that many of these dress codes do not accommodate tribal wear when necessary.

You can’t heal or reconcile until you shut down the genocide completely.

It’s a long, slow road we travel — far too long and far too slow. I hope very strongly that things will change.